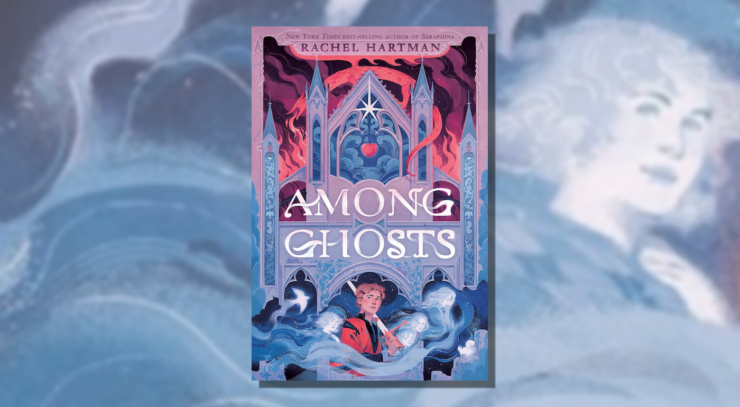

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Among Ghosts, a new young adult fantasy novel by Rachel Hartman set in the same world as Seraphina, out from Underlined on June 24, 2025.

A few things to know about the town of St. Muckle’s: It’s too out-of-the-way to interest greedy lords, and too damp and muddy for marauding dragons to burn. And anyone, from a humble serf to a runaway nun, may earn their freedom by living for a year and a day within the town walls. Seven years ago, Charl and his mother fled to St. Muckle’s and made it their safe-haven, building a new life in this so called Peasant’s Paradise. But when Charl sees something impossible—a ghost—soon the embers of his past are threatening to engulf his world in flame. A tragic accident is quickly followed by murder, a deadly plague, and a mercenary dragon.

Charl manages to escape to an abandoned abbey outside of town, but finds no safety within those ruined walls. A treacherous nun, a chorus of murdered girls, and the fearsome Battle Bishop await, ready to ensnare him in a complex web of history, magic and fate. For some things should never be forgotten, however much they haunt us, and Charl will need all his wisdom and resiliency if he is to fight for the world he knows… and the people he calls home.

A brief introduction to the excerpt from author Rachel Hartman:

Once upon a time, a pandemic left me feeling haunted. Maybe you’ve felt it, too.

When lockdowns hit, I decided it was the perfect time to finally read The Decameron. Was I not holed up against the plague, desperate for stories to distract me while the world burned? I didn’t get far, partly because Bocaccio’s tales have not all aged well, but mostly because an idea soon caught me: what if I borrowed this conceit for a book set in the world of Tess and Seraphina? I started writing about a boy and an elderly nun, hiding in a haunted monastery, telling each other folktales.

That’s not where Among Ghosts ended up, however. I quickly discovered that while folktales were fun, I was much more interested in everything Charl and Mother Trude had gone through to get to that monastery—treachery, plague, and dragon fire—to say nothing of the abbey’s ghosts.

There had never been ghosts in Goredd before; Seraphina and Tess didn’t believe in them, and frankly, neither did I. Maybe I had to come humbled and pre-haunted to finally see them.

Maybe I had to experience that same helplessness, trapped between the living and the dead, unwilling to remember and unable to forget, before I could hear their voices. I’m glad I finally did, because they became the (un)living heart of this book. I hope they shine for you like they shine for me.

(And if you’re wondering what became of all the folktales, well, some made the final cut and some did not. The ones that didn’t fit now have a home of their own at my Patreon, Fake Folktales.)

1

The Old Abbey

North of St. Muckle’s, overlooking the muddy valley of the Sowline River, the crumbling Abbey of St. Ogdo’s-on-the-Mountain hulked darkly in the predawn mists. The monks had abandoned the place long ago, and the forest had moved in to reclaim it. Even if you didn’t believe in ghosts—and what sensible person did?—it looked haunted. The jagged remains of broken towers poked into the eye of the sky, vines slithered over the thick stone walls, and the wind, blasting down from the craggy heights, moaned and sighed among the ruins.

Into this desolate place came three lads. Finding the front gates locked, they set about climbing the ivy-tangled walls.

The first to the top was a tall, handsome fellow, leader of this covert expedition—Rafael, called Rafe, the son of Lord and Lady Vasterich. He paused upon the battlements, rubbing ivy sap off his hands, trying to catch his breath and gauge how much time was left until sunrise. About an hour, by his reckoning, but broody, low-hanging clouds obscured the sky and made it hard to tell. The clouds spat drizzle at him. Rafe wiped his face with his fine linen sleeve and pretended he wasn’t furious.

But he was. If he’d wanted to wallow in the mud, he could have stayed in St. Muckle’s. He’d come here to fight a duel at dawn, and the sky was supposed to be a dramatic red.

The ruins spread below him, within the encircling arms of the wall. Dragon-fighting warrior monks had once lived in this abbey, led by the notorious Battle Bishop, back before dragon fighting had become the exclusive domain of knights. Hence the battlements. They’d built this place to last. Even so, after two hundred years most of the roofs had collapsed, as well as some of the smaller buildings. A grove of pale birch trees had pushed through the broken flagstones of the courtyard; vines and weeds choked every other available space.

Hardly anyone came here anymore. From St. Muckle’s, nestled among muddy turnip fields in the armpit of the valley, it was a several-hour hike up the mountainside; from Fort Lambeth, on the north side of the mountain, it was even farther. This isolated ruin was the perfect place to kill someone, although not—Rafe had learned—ideal for hiding the body.

Rafe had selected his two comrades, Wort and Hooey, for size and strength; they were only now reaching the top of the wall. They flopped onto the battlement, gasping like fish out of water.

“You didn’t tell us we were going to have to climb the blasted ivy,” cried Wort when he had recovered enough to speak. He was a well-muscled lad, good for landing a punch, but apparently not so nimble on a vertical surface.

“Someone locked the gates,” said Rafe disdainfully. “They weren’t locked the last time I was here.”

“It was probably the Busybody Brigade, trying to keep people out after that boy fell down the well,” offered Hooey. He was narrower, wiry, and trying very hard to grow a goatee, which made his face look smudged from a distance. “Remember that boy who drowneded a couple years ago? John Eel-Hook?”

Rafe glared across the ruin and didn’t answer. He remembered that boy, more vividly than either of these louts possibly could. Rafe remembered him screaming.

Without another word to his companions—they weren’t friends; he didn’t have friends—Rafe turned and strode along the battlements until he found stairs down to the courtyard. The other lads scrambled to keep up.

“I remember John Eel-Hook,” Wort was saying. His mess of curls made him look like a sheepdog. “He’d been dead a week before they found him.”

They—the people who’d found John Eel-Hook’s body—had been a convoy of traveling Porphyrian merchants. Apparently, they made a habit of stopping at the Old Abbey to water their horses before the last leg to St. Muckle’s. The horses had shied away from corpse water. Horses could always tell.

Those same Porphyrians were probably the ones who’d locked the gates, in fact, and not the Concerned Busybody Brigade of St. Muckle’s (accursed meddlers). Rafe scanned the courtyard from the bottom of the steps and saw that the Porphyrians seemed also to have put a wooden cover over the mouth of the well, to stop anyone else from stumbling into it by accident.

Everyone had assumed John Eel-Hook had drowned. His body had been so bloated that not even that dragon doctor (disgusting person) could make out his cuts and bruises.

And, to be fair, the boy’s death had been an accident. Rafe had only meant to teach him a lesson about respecting his betters. Things had gotten out of hand.

Charl’s death wasn’t going to be an accident, though.

Buy the Book

Among Ghosts

“So what’s the plan?” said Hooey, strolling out from under the birches into the weedy half of the courtyard. He dropped his rucksack and rolled his shoulders.

“There’s a sally door in the gate,” called Wort, who had wandered that way. He meant the smaller door set into one of the larger wooden gates. That entrance wasn’t padlocked, merely barred from the inside. Wort unbarred it without asking permission. “I’ll leave it a bit ajar,” he said, “so the kid won’t have to climb the wall.”

Rafe gritted his teeth at this show of unnecessary consideration. Wort had no business taking such initiative—and how dare he call Charl a kid? That so-called kid was not some artless innocent. He wasn’t a child; he was thirteen years old, albeit short for his age. Kid suggested that Wort (soft-hearted imbecile) sympathized with him, and sympathy was trouble. It made people balk from doing what was necessary.

Not for the first time, Rafe questioned his decision to bring these two clowns (boneheaded peasants). They seemed as likely to be a liability as an asset. But if he did this right, they’d feel too guilty to talk. They’d be implicated in everything, and they’d be highly motivated to give him an alibi.

“What’s the plan?” Hooey repeated. “Smack him around? Scare him a bit?”

“I mean to challenge Charl to a duel,” said Rafe archly. “With swords.”

Wort and Hooey burst out laughing. Rafe bristled like a cat.

“What swords?”asked Hooey, gesturing extravagantly at Rafe’s waist, where no sword belt hung. “Did you leave them at home?”

“They’re in the sanctuary.” There was only one sword in the sanctuary, in fact, but these louts didn’t need to know that.

“Isn’t this the kid who beat you at swords once already?” said Wort, sitting on a rock that looked uncomfortably pointy. “Guess I won’t feel too sorry for him, then.”

“Those were just wooden swords,” said Rafe through clenched teeth. “Besides, his mother was standing right there. I couldn’t very well go after him with my full strength.”

That wasn’t quite what had happened, though. In fact, Rafe had wanted nothing more than to see Charl’s mother weep— that meddlesome woman, that foreign interloper who’d turned the rightful order of things upside down. She’d been a constant thorn in his family’s side. Rafe had kept an eye on her all tournament long. Whenever her precious little Charl was in a skirmish, she had covered her eyes, hardly daring to peek through her fingers. Rafe moved up the tourney ranks and did what he could to make sure Charl also advanced. It had meant sabotaging one lad’s handgrip and another’s pants, but none of that put the slightest crimp in Rafe’s conscience. He’d had a loftier goal: to face Charl in the final and “accidentally” put out his eye.

Charl’s mother, that busybody innkeeper, Eileen, would collapse screaming. She’d take her precious baby and go back to Samsam, and everything would revert to the way it was supposed to be. The Vasteriches would be on top again; the low-born would remember their place.

Alas, it had all gone wrong. Eileen (redheaded witch) had been joined by her friend the ex-nun (obnoxious know-it-all), who’d bolstered and cajoled her into watching without her hands in front of her face. And Eileen’s face—damn her to the Infernum—had proven too great a distraction for Rafe. He’d wanted to catch her eye, to smile right at her as he popped her precious son’s eyeball from its socket. He’d wanted to watch her melt into agonized grief and savor every moment of her pain. So intent had Rafe been on keeping the mother in his sights that he had vastly underestimated the son, who’d slipped through his defenses and won the match.

And, of course, everyone in town took it as emblematic of the new order of things. The heir of the landed gentry (Rafe) bested by the brat of the incorrigible idealists who were turning St. Muckle’s into a peasants’ paradise. The rabble had taken Charl up on their shoulders and paraded him through the streets, hooting and cheering.

No matter.Let the pathetic fool keep his pathetic victory.There was one thing Charl still didn’t have that he desperately wanted. Even supposing someone of his class could afford such a thing, his idealistic mother (laughable pacifist) would never let him have it.

A real sword.

That was how Rafe had lured him up here. Meet me at the Old Abbey at dawn, and I will show you what I found. The sword of the Battle Bishop himself, lost for two hundred years.

Rafe hadn’t added, And then I will stab you dead with it. That part would be a surprise.

“So, what’s the win condition for this duel?” Hooey was a gadfly, buzzing in his ear. “Will you use corked sword tips and fight to five touches?”

“Or uncorked tips, fighting to first blood?” Wort interjected, ghoulishly cheerful.

That was the kind of bloodthirsty enthusiasm Rafe had been hoping for. “Uncorked, until he learns some respect for his betters. Until he’s in ribbons, if that’s what it takes.”

Wort and Hooey exchanged a sidelong glance, suddenly looking wary. Rafe did not understand why they should.

It was probably the word betters. Perhaps he shouldn’t have said that, in front of these two. Certainly, their families were well off—almost as comfortable as his, at the moment, although that would surely change. The Potters and the Tilers were respected artisans in town, but everyone knew they came from dirt-common peasant stock. Three generations as free townsfolk (what a joke) didn’t change their essential natures.

“There are plenty of ways to scare him without slicing him to ribbons,” said Hooey at last. “I bet he’d poop his pants in terror if he fell down the well where John Eel-Hook died.”

Again, treating Charl like a little kid. “He’s not a baby,” snapped Rafe.

“Oh, cack!” cried Wort, using a childish word of his own, a peasant’s idea of cursing. He sounded relieved, though. “D’you think John’s ghost is still down there?”

Three generations in town hadn’t driven all the foolish peasant superstitions out of their heads, either. “There’s no such thing as ghosts,” said Rafe sternly.

“I know,” said Wort, squirming in his clothes. “I was joking.”

“We’ll need a rope, to pull him out when he’s had enough,” said Hooey, hands on his hips, looking around for one. It was still too dark to see much. “Wort, help me with this lid.”

Rafe, disgusted, left them struggling with the well cover. This was turning out worse than he could have imagined. Not only were they unexpectedly shying away from bloodshed, but they were coming up with alternative plans of their own. Rafe needed them to understand what a blight Charl was upon the natural order of things. That he needed to be put down.

“You can’t just come to St. Muckle’s and become anything you want,” Rafe grumbled to himself. “People are born to their proper stations, and should accept that.”

Rafe walked the perimeter of the courtyard until he found what he was looking for: wagon tracks leading deeper into the ruin. It had occurred to him that the Porphyrian traders who’d stopped here for water might also store things here, and since one of the things they imported to St. Muckle’s was spirits— liquor, that is, not ghosts—it was worth checking to see if they’d stashed any away. Wort and Hooey (intemperate clods) were not the sort to say no to a drink. It wasn’t Rafe’s fault if it was stronger than they were used to.

With a little pisky in them, they’d be more biddable. They’d do things they wouldn’t do under normal circumstances. They’d be ashamed, afterward, and would never tell anyone what had happened.

The tracks led to a sturdy cellar door of new construction, like the well cover. Rafe grinned joylessly. This was the place. He flung open the door and descended some wooden steps. The cellar was full of crates, and each crate held a dozen ceramic jugs, stoppered with corks. Enough pisky to pickle every liver in town twice over.

Well, not Rafe’s. He would never allow himself to be impaired in such way. He didn’t even like the smell of pisky.

He lifted a jug and carried it back to the lads.

They’d been busy in his absence. They’d dragged the well cover off to one side, located the bucket and draw-rope, and then—absurdly—built themselves a cheery little campfire. The courtyard looked set for a picnic, not a deadly duel.

Rafe swallowed his rage and reminded himself that everything would be back under control once these buffoons were drunk enough. He wrestled his expression into a smile—which felt wrong, and hurt a bit—raised the jug, and called out, “Look what I’ve found!”

Wort and Hooey were at the edge of the birch grove, trimming slender birch switches for themselves. Rafe could not imagine what they intended to do with those twigs. Trip Charl, so that he fell into the well? Whip at him futilely? Anyway, the lads looked up when Rafe called, and grins spread slowly across their faces as they realized what he had.

“There’s a welcome sight!” said Wort, stepping toward Rafe.

“Toss it here,” said Hooey, holding up his hands.

Rafe lobbed the jug softly to Hooey.

It was not a bad throw, but something happened as the jug arced through the air.

A pair of eyes glinted from the open sally door behind them.

And a woman stepped out of the birches, so pale she was almost transparent, wearing a mournful expression and an old-fashioned gown. She walked right through Hooey as if she hadn’t noticed he was there.

Hooey froze, a horrified look on his face, and failed to close his hands around the jug.

The jug landed at his feet and exploded into a massive fireball.

It completely engulfed Hooey. Hooey was gone in a flash.

Flaming liquid spattered all over the courtyard. Some hit the nearest birches and set them on fire. Some spattered onto Wort, who started screaming. He dropped to the ground and rolled in the weeds, but that didn’t extinguish the flames. It only spread them.

This wasn’t the sort of fire you could put out that way, Rafe recognized dimly. The jugs weren’t full of pisky after all. They were full of pyria—the sticky, highly flammable oil that knights used for killing dragons.

Wort ran toward Rafe, trailing flames and screaming. Rafe cringed, flinging his arms up around his head like a coward, but Wort wasn’t coming for him. Wort, in desperation, flung himself down the well.

You couldn’t extinguish pyria that way, either. Rafe, shocked and sickened, stood at the lip of the well and watched the flames rage under the water. The water boiled.

Nausea roiled in Rafe. He turned his back on these horrors and staggered off.

“I didn’t know,” he muttered. The flaming courtyard raged behind him. “I didn’t do it. He should have caught it.” Unseeing, he stumbled deeper into the ruins. “They were too stupid to live. They were going to ruin everything.”

Ahead of him, between the hulking shadows of the ruined buildings, a little light shone. Twinkled. A welcoming light, unlike the towering inferno he’d left behind him. Rafe walked toward it, drawn like a moth.

“They were just peasants,” he whispered.

Come closer, the light whispered back.

It was a candle flame, he could now see, set up in the window of the sanctuary. The whole monastery lay crumbling around him, but the sanctuary still had glass in its windows. It still had its big wooden doors. They opened soundlessly at Rafe’s touch.

He’d been here before, he recalled vaguely, but it hadn’t looked like this. Now every lamp and candle was lit, dazzling his eyes. The wooden trim was newly lacquered, the gold leaf restored, the cobwebs cleared away. Bishop Marcellus’s cadaver tomb no longer had ivy crawling all over it but gleamed alabaster white. Rafe didn’t question these changes; they seemed to make sense, the way a dream makes sense.

He entered like a sleepwalker and stepped toward the altar, where the candles burned brightest. Someone was there, a bulky, shadowy figure kneeling in prayer. Rafe’s heart turned to ice, but he kept walking, because he could not stop.

“I didn’t mean to kill them,” said Rafe as he neared the altar.

So, who did you mean to kill? said a voice that made his insides ripple like water.

The figure rose. It was a smoke-colored blur, a smudge in the air, except for the eyes. The eyes were two dark pits that seemed to lead downward forever, down to someplace cold. Rafe felt himself teetering, as if he were standing on the edge of a precipice. As if he might fall into those bottomless pits.

“They were idiots,” whispered Rafe, trying to delay the inevitable. “People get what they deserve.”

I agree. But tell me: What do you deserve?

Rafe whimpered, too terrified to speak.

Two shadowy hands reached out and grasped Rafe’s head. The icy fingers pressed deeply, pressed all the way into his mind, and he screamed.

And screamed.

Outside, the petulant clouds burst forth in rain.

Excerpted from Among Ghosts, copyright © 2024 by Rachel Hartman.